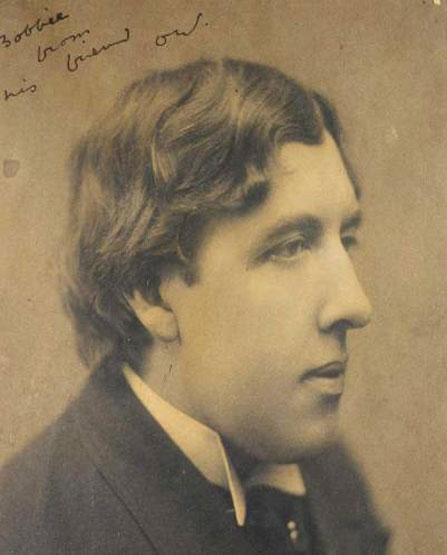

When I first saw the Wilde ambrotype, my attention was drawn to the hat. I did not think the sitter was Wilde, but rather a young man making a conscience attempt to copy the appearance of Oscar Wilde.

It was only after examining the enlargement print that I realized the young man was none other than Oscar Wilde himself!

The hat is chic. In a later version the brim is larger, and the crown elevated and reduced in size. However, the hat’s essential style remained.

There are two more aspects of his attire that should be noted-his white shirt collar and bow tie. While the lay of the collar is identical to later images, this bow tie is discreet, unlike its later flamboyance.

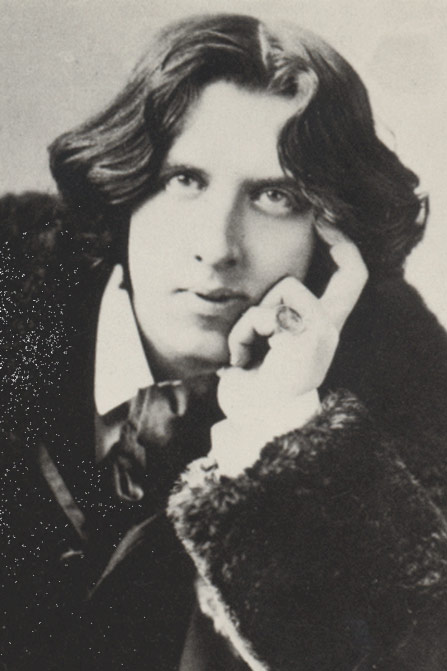

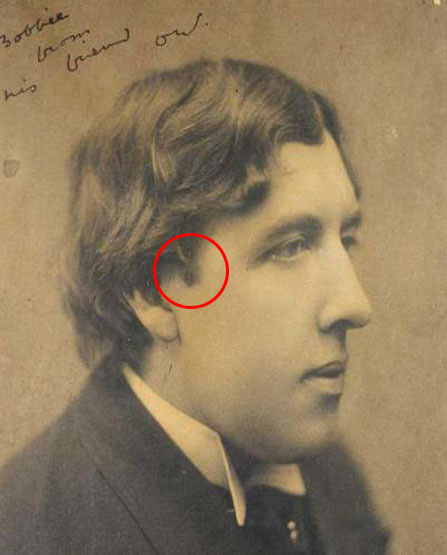

If the viewer will compare known photographic images of Oscar Wilde with the ambrotype, the following will become apparent: The philtral columns, and their joining with the upper lip are identical; the eyebrow is identical; the upper eyelid is identical; the chin is perfect; the nose is perfect; the lay of his hair is excellent, the ear lobule is identical. A very uncommon point of similarity is a small tubercle located in the middle of the Tragus.

While the forensics are good, even very good, we are, nevertheless, left with an image that does not remind us of Oscar Wilde. This is not uncommon with early photography. A well-known example of early photography distortion is the 1848 Lincoln daguerreotype in the vault of the Library of Congress, known as Meserve # 1. Leading 19th Century Lincoln scholars, including Albert J. Beveridge, [not knowing that it had been in the possession of Robert Todd Lincoln, who gave it as a gift to Frederick Hill Meserve], understandably scoffed at the image, declaring the man of the daguerreotype was not Abraham Lincoln.

| Kaplan Collection | Known Images |  |

|

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sideburn

He had a unique sideburn. See the comparison below.

| Kaplan Collection | Known Image |  |

|

|---|

Having examined well over a million daguerreotypes and ambrotypes images, I seem to have developed an eye for identifying street-made images. My first impression of this image remains. It is not studio-made. Its small size, ninth plate, reinforces that opinion, as does the unquestioned distortion caused by a poor quality lens.

Grant Romer, the recognized world authority of early photography, examined the ambrotype, and told me that the case is definitely of American origin. Normally, he would have opened it up for a minute examination. However, he declined to do so because of its poor condition. He told me that its condition was so poor, there was a fair chance that he would not be able to put it back together again! Accordingly, he did not lift and clean the glass, and examine the plate which might have revealed its origin. He told me that the overall package is not likely original. Moreover, he told me that without a doubt there had been previous intervention.

Thus, I cannot say whether the image was made in the United States during Wilde’s 1882 American tour, or whether the image was made in Britain or the Continent. However, wherever it was made, it is almost certainly the production of a street ambrotypist.

During the last 37 years as a reasonably well known collector of early photography, I have communicated with a number of fellow collectors, dealers, museums, societies, auction houses, and the like. In every instance those contacts and relations were cordial. Until two men in England, Messrs. Michael Seeney and Merlin Holland (Oscar Wilde’s grandson), representing the Oscar Wilde Society, initiated contact with an auction house who had agreed to offer the ambrotype.

According to the auction house, Messrs. Seeney and Holland declared that the man of the image was not Oscar Wilde. As this emphatic declaration came from officers of the Oscar Wilde Society, the auction house decided to delist the offering.

It has been suggested that the reason they communicated with the auction house was because they considered it their civic duty to prevent what they believed to be a fraud perpetrated on the unsuspecting public. It has also been suggested that the reason they contacted the auction house was to try, in such a questionable manner, to maintain their apparent monopoly over photographic images of Oscar Wilde. I do not know why they took the action they did. But, I do know that they overstepped the boundary of thoughtfulness and gentlemanly conduct.

I considered taking legal action against them. However, the cost of mounting such a lawsuit, of necessity through the British courts, was so great, I decided, with painful reluctance, not to do so.

I may, in the future, put this ambrotype up for auction, perhaps at one of the well known American or British auction houses. What follows is a message to that auction house:

“Before you agree to list this ambrotype for auction, know that you may be contacted by these two characters.”